|

Video Credit: Sam Morell of XRT-C On 7th July, it was officially announced that Bodmin Moor and the peripheral areas had been designated as an International Dark Skies Landscape. This was the culmination of three years’ arduous work collecting vast amounts of data which led to a comprehensive application, jointly submitted by Cornwall Council and Caradon Observatory to the International Dark Skies Association, in Tucson. Significantly, this was the first time that an Area of Outstanding National Beauty (AONB) had been successful.

...

0 Comments

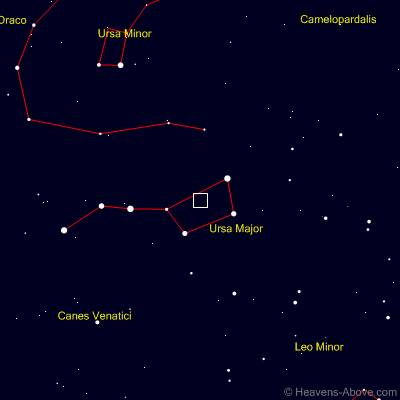

Here's a quick animation from the night of 24th/25th March showing the movement of Comet 41P against the background stars. Each frame is a 2 minute exposure taken with a 135mm lens, the time-lapse is two hours long. On the 24th March it was visible in the bowl of The Big Dipper, or business end of The Plough if you prefer. The bright stars of this famous asterism are just out of frame. Over the next few days it moved into the neighbouring constellation of Draco. Comet 41P goes by the name of Tuttle–Giacobini–Kresák which is a bit of a mouthful. This is because comets are typically named after their discoverers, 41P was independently found in 1858, 1907 and 1951. It is a short period comet which approaches the Sun every 50 years or so and is thought to have a nucleus about a mile across. The comet has a circular appearance rather than showing the classic cometary tail because of the viewing angle.

...

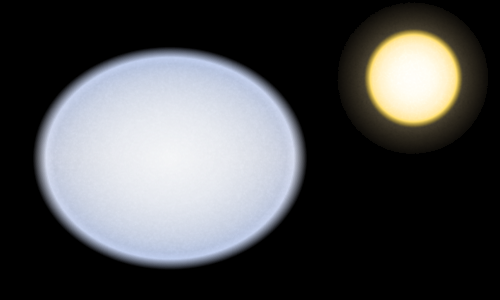

Rising to the East at this time of year, the three stars of the Summer Triangle are bright enough to punch through twilight and even a little wispy cloud. To the naked eye they appear as three white/blue points of similar brightness, but this is deceptive.

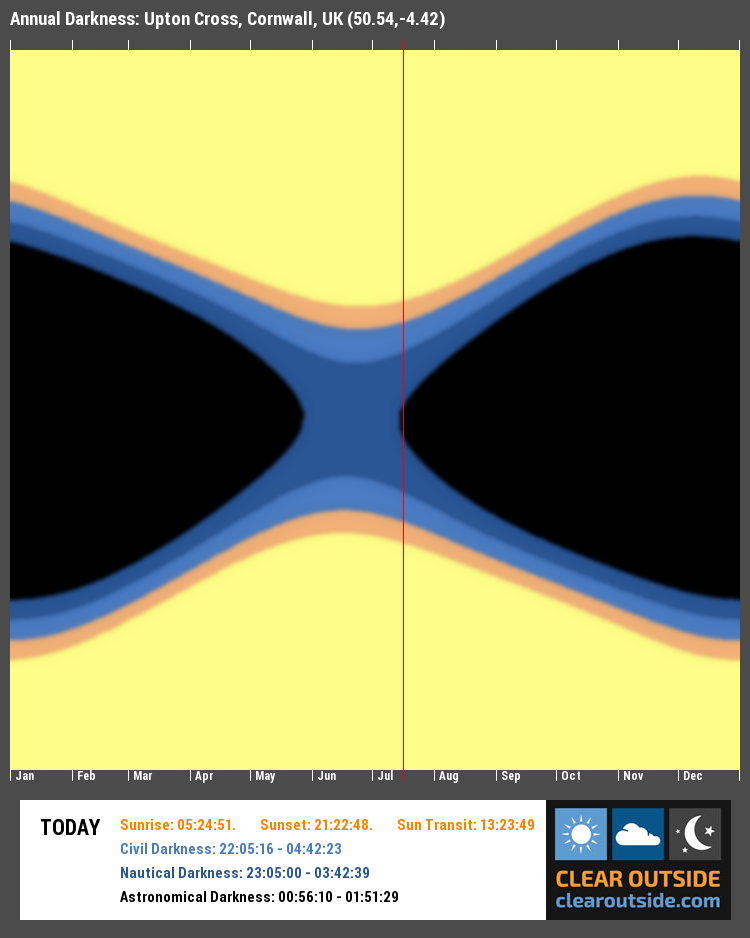

The two stars on the right of the image - Vega and Altair - are indeed quite similar. They are both A-class stars, more massive and more luminous than the Sun. As residents of our neighbourhood they are among the brightest in our sky. The most surprising thing about Vega and Altair is: they are not round. They aren't even close to spherical. Full astronomical darkness is now returning to the southern UK. Here's a chart from FLO's Clear Outside showing annual darkness for Bodmin Moor. In the blue portion of the chart, centered around Midsummer, the sky never becomes fully dark. At that time of year the Sun never drops very far below the horizon, so the upper layers of the atmosphere are still lit up in an extended twilight. This isn't easily noticeable from brightly-lit towns and cities but is quite obvious from a dark, rural location. Astronomical images taken outside of astro-dark have a blue tint and are washed out to some degree by the reflected sunlight. The 15 second exposure above was taken on the 18th June in SE Herts, at about 11:30 PM. The yellow colour at the bottom right is caused by light pollution, probably from the town of Bishop Stortford.

Practical astronomy with an almost-seven year old?  Spent some time with nephew-nearly-seven over Christmas and - despite the lure of lego ninjas and talking dinosaurs - he was quite happy to join me outside on a clear and frosty night. I started off by showing him a few landmarks of the sky - the Milky Way, most prominent stars and recognisable constellations - using a laser pointer to trace out their shapes. (After first explaining the importance of checking for aircraft, to avoid dazzling them. He certainly made a conscientious air traffic controller, for the rest of the evening I couldn't go near the the laser without a warning, including for planes fifty miles away and in the other direction.) Resting on the Pole star I tried to explain how the stars appear to rotate around it, as shown in the time-lapse video below. Video by James Castelli, Cherry Springs, Pennsylvania - Aug 2008 Next we had a go at astrophotography, I set up a motorised tracking mount and attached a camera with a wide lens. I pointed the camera in roughly the right direction and disengaged the clutches so he could gently nudge it on to target. After a couple of attempts he got this shot of the Milky Way with a 2 minute exposure.

When thinking of deep sky objects (DSOs) - distant nebulae and star clusters within the Milky Way and even more distant galaxies - it's natural to assume that a large telescope is required to view them. In many cases this is true, where the vast sizes of these objects is trumped by the even greater distances to them. However, there are a number of DSOs - relative neighbours in cosmic terms - that occupy surprisingly large slices of our sky. The gallery below shows a number of fairly bright DSOs along with the Moon, to show their relative apparent sizes.

Here's a set of images comparing light pollution between Crowdy Reservoir on Bodmin Moor, Cornwall, and south-east Hertfordshire, about a mile north-east of the town of Ware.

The montage shows the progression of the September 2015 lunar eclipse over a period of about two hours, as Earth's curved shadow passes across it. Unusually, this eclipse coincided with a so-called supermoon, where the full moon is at the closest point in its orbit and appears slightly larger to the eye - such an event will not occur again until 2033. At totality the Moon is still visible as some sunlight still reaches it by passing through the Earth's atmosphere. However, it appears much dimmer and redder than normal - at a second the final exposure in the sequence is 1,000 times longer than the first. The deep red colour is caused by the same phenomena that makes our sky blue - our atmosphere scatters blue light more readily so that more red light reaches the Moon's surface, and is reflected back to Earth.

Taken by Ken Bennett, with the aid of a 5" refracting telescope, DSLR camera and some choice Cornish cursing-words. |

Archives

May 2020

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed